1.

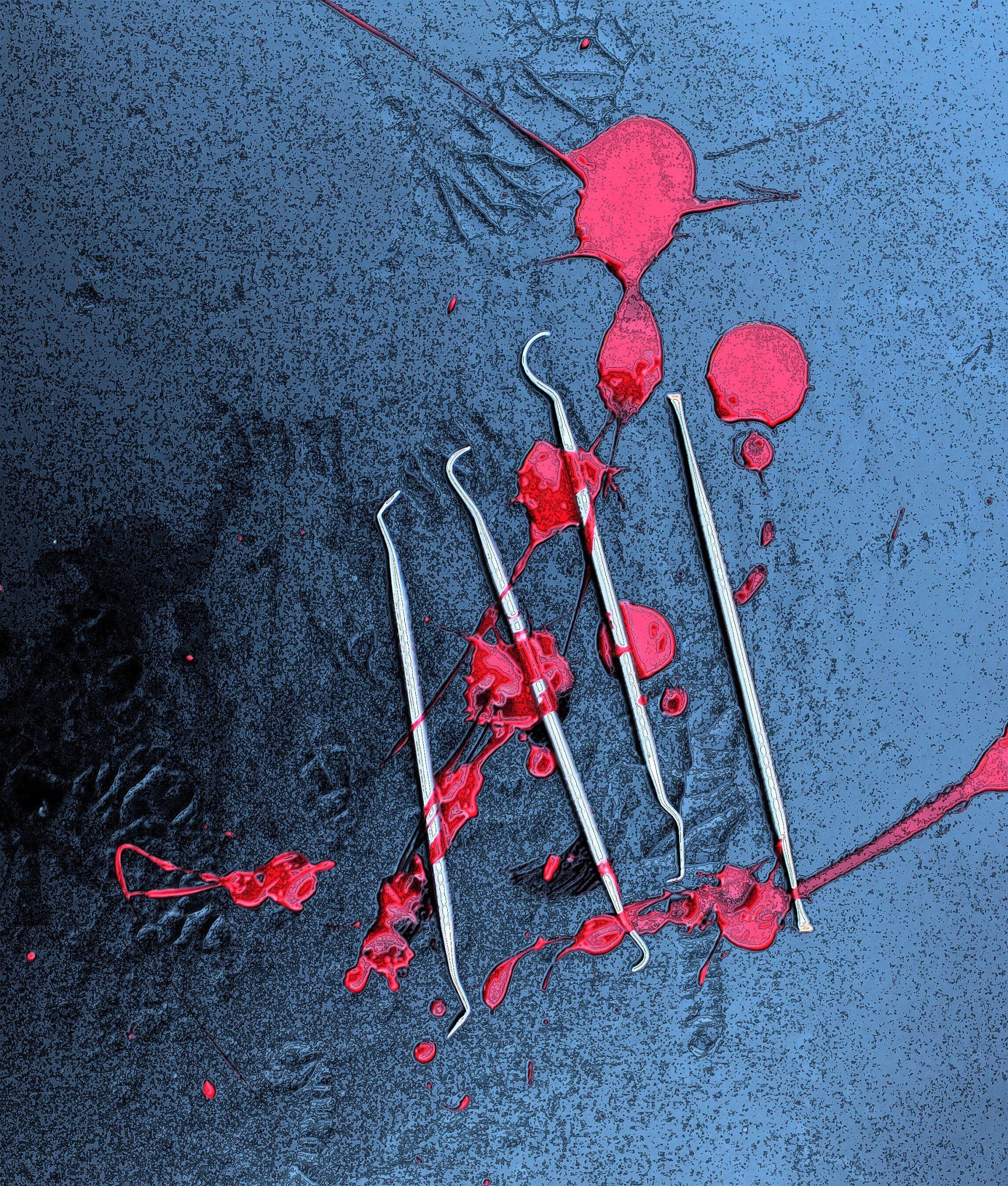

Chisels, Hatchets, Scalars

DENTAL. PICKS AND SCRAPERS. They decided to begin hard. It had to be torture. They set out first thing in the morning to research kits. They met in the lobby cafe of the university hotel and ate melon stabbed with toothpicks. They cut into ligamental pineapple with spoons. They used doll-sized saucers to catch the drips and sloughed off membranes and kept the keyboard clean.

The younger man paused and rubbed his fingers over the keys. “I don’t know if I want these words to become part of my recorded history.”

“No worries,” said the professor, “they will be. This is to be the next grand narrative.”

The professor admitted he had already searched last night and found some impressively nasty looking instruments on auction sites, tools splotched with rust and flecked with years of avid use. His chief concern, though, was the transaction — the recorded purchase of the tools, and all the self-aware chitchat he would have to endure if anyone were to discover the items of his purchase, along with all of the irresistible probing questions that come with it, so he told his assistant, "Dental." Simple. That’s where they began.

They were immediately pleased to find that stainless steel picks and scrapers come cheap for the hygiene enthusiast, but luckily there's also a thin market for more complete dentistry sets, priced for those doomsday-preppers worried about abscesses beyond kingdom come. The professor's research budget was tiny — it had been tricky to couch the words for experimental torture in this day and age — so they ordered the most varied and cheapest set, unbothered by craftsmanship: plastic handles instead of metal, warped hinges, edges a little rough for clean tissue laceration. It was appearances they were interested in. Big cutting, slicing and gripping tools. The assistant offered to pick up pliers and a vise grip from the hardware store, until he remembered he had these already at home, and would bring them tomorrow.

The contract paperwork outlining the parameters of Friday's session was an essential part of the experiment. The professor enlisted the help of a friend from the English department, an Emma Lazarus scholar, to act as a lawyer. The subject, the woman they would torture, had never seen this man, nor anyone from the college beyond the professor and his assistant, only the backs of persons she'd avoided at gas stations and parking lots. So when she entered the Louis Pasteur room of the university library, she paid little attention to the man costumed in a lawyer's suit and busy stacking legal pads on the table a little too theatrically. She dropped into her chair and pulled in her legs, heels crossed and knees splayed to the arm rests. Her remarkable poise and self-possession arrested the professor and alarmed his young assistant. As if recalling a delightful memory on the sudden wind of unexpected association, she snatched out of her hip purse a small bag of apple slices, split the bow of one with her front teeth with a pop, and tucked the mash into her cheek, chewing in the slow rhythm of a daydream. She looked up at them. She was ready when they were.

The man beside her was searching for his pen in the pit of a creased briefcase that he’d borrowed from his father, an actual lawyer. They sat around a narrow table in one of the private reading rooms off to the side. She chewed and watched them set up.

Dr. Thomas C. Hock, Professor of Thought and Consciousness and chair of the Curriculum Design Committee, along with his teaching assistant, Stuart, sat opposite the makeshift lawyer and their test subject, Ms. Veronica Samir. Hock had first been made aware of the subject by the beguiling reports he had heard of her from an old colleague. She had signed up to become a research assistant on an expedition to Ecuador, a dream quest and gathering of vocalizations made by howler monkeys. She herself didn’t put too much stock in the storybook decoding of animal prose, but she had been promised a good hike. She had been bouncing around the graduate departments of George Washington searching for something. One adviser described it as an endless, neurotic self-interrogation of the nature of her desire, but it is well known that this man lacked imagination. She partook of all disciplines — from sleuthing electronic bank fraud to investigating animal mutilation — because such radical changes piqued her remarkably agile mind. She was dissatisfied with the inherent resignation of specialization. So when she saw an opening for Ecuador, she jumped once more, and made a spectacle of her time while she was there.

She double-roped to the crowns of giant ceiba trees, and when she twirled in suspension a hundred feet in the air, the gear seemed incidental. On one exceptionally windy evening, after her colleagues had rappelled down for the night, she swung over to a portaledge and called for them to send up a book and a light.

She got up close to the backs of anacondas to examine the plated intricacy of their scales, kept jars of wandering spiders, and played one prank on the safety manager with a giant centipede. When the whole expedition was nearly shut down by ethnic conflict in Tiputini, she went out to pick blackberries in the middle of the hot zone; the whole conflict seemed to resolve as quickly as she had emerged in the clearing, and that coincidence became a source of increasingly contentious cabin debate. Flash floods, bloodshed between tribes and twitchy government forces, even a nighttime earthquake, she never lost her cool, never showed worry, never looked for a retreat. She just floated. The project lead suggested she was fearless, and took the opportunity to discuss that suspicion on the flight home. He asked her if she’s ever known fear, the sort of fear that makes a heart jet with blood, that ties up the cerebral cortex and sends common phobia into waves of panic. She said, “I don’t know, not really.” Intrigued, he set up a fear-conditioning test at the school, and after intensifying the stimuli, they found no physical markers of distress. “Maybe she is fearless,” he told Hock, and maybe she would make the ideal test subject for his pet project.

She had begun to wonder if her fear response was all that unusual when the professor contacted her. When he explained what he hoped to achieve in the study, what it might do for the direction of the university, and of her role in it, she paid attention. When she learned the nature of the experiments he had in store for her, she showed interest.

In the private reading room, sitting at the long, narrow table, the professor explained, “While the experiments border on the extralegal, it is important to delineate the boundaries of what we will and will not do to you.” He explained that while they deliberately will set her in situations of great emotional and physical danger, they would not inflict pain or suffering directly. “That will be left to chance, and to the whims of the public.”

She held a look of suspicion, less of doubt than of curiosity. “To chance. Go on.”

“In each of these trials, experiments, these ordeals, we will depend on the variability of strangers. These will be public. People will see the straits, the peril you are in. Whether or not they help you avoid physical harm is up to them, people we don’t know, the public.”

The Lazarus scholar had been drawing zigzagging triangles on his legal pad, filling in the tips with points of slick, black ink. He did his best to stay in character. “Extralegal,” the professor had actually said. He wondered what else would be said in that room, with him as a witness, and collaborator.

“The public will know you are in grave danger. It will be up to people to do something about you. Sometimes it will be up to people to save you. And sometimes it will be up to people to stop themselves from hurting you.

“The variable,” his whole face smiled at the grand, sweeping oath he was about to make, upon the fortune of circumstance and the arrangement of words that had led him to this point, “is human nature.”

The pretend lawyer stopped hemorrhaging ink and looked sideways at her. She looked over to the assistant. She was grinning at the theatrical absurdity of the moment, the ridiculous conception, the delivery in a small, private room.

“What do you think?” she asked the young man sitting next to the professor.

Stuart had all this time been watching the small changes in her face.

“Okay, I’ll try one,” she said.