3.

Fallen

FROM THE FIFTH FLOOR of the Ron J. Stein building, sixty feet above the cobbles and the umbrellaed tables of the Wilson Center, they surveyed the composition of the scene. They did not want to be shut down. Police were so busy chasing aftermaths of gunfire and responding to complaints of post-apocalyptic bike gangs and heated clashes over church parking that they knew, with a little fortune, they could pull it off on time. They further mitigated chances of emergency calls by dressing up the performance in vests, t-shirts, sandwich boards and banners emblazoned with the seals of the Smithsonian, the Corcoran, and the Kennedy Center. These were mocked up by the art students, Doc Hock’s enlisted corps of graphic artists, photographers, painters, sculptors, thespians and set designers. They concocted a title for the show: The Dissolution of Human Flight, and drew up an emblem, a somewhat cartoonish figure of a witch set high on a platform, a line connecting her to a monochromatic mob below.

In the square they had wired together a bank of screens, a video installation, discreetly portaged by hand trucks and easily assembled. There was one eye-catching focal point on each of these screens, a woman in a red flowing dress, high on a ledge.

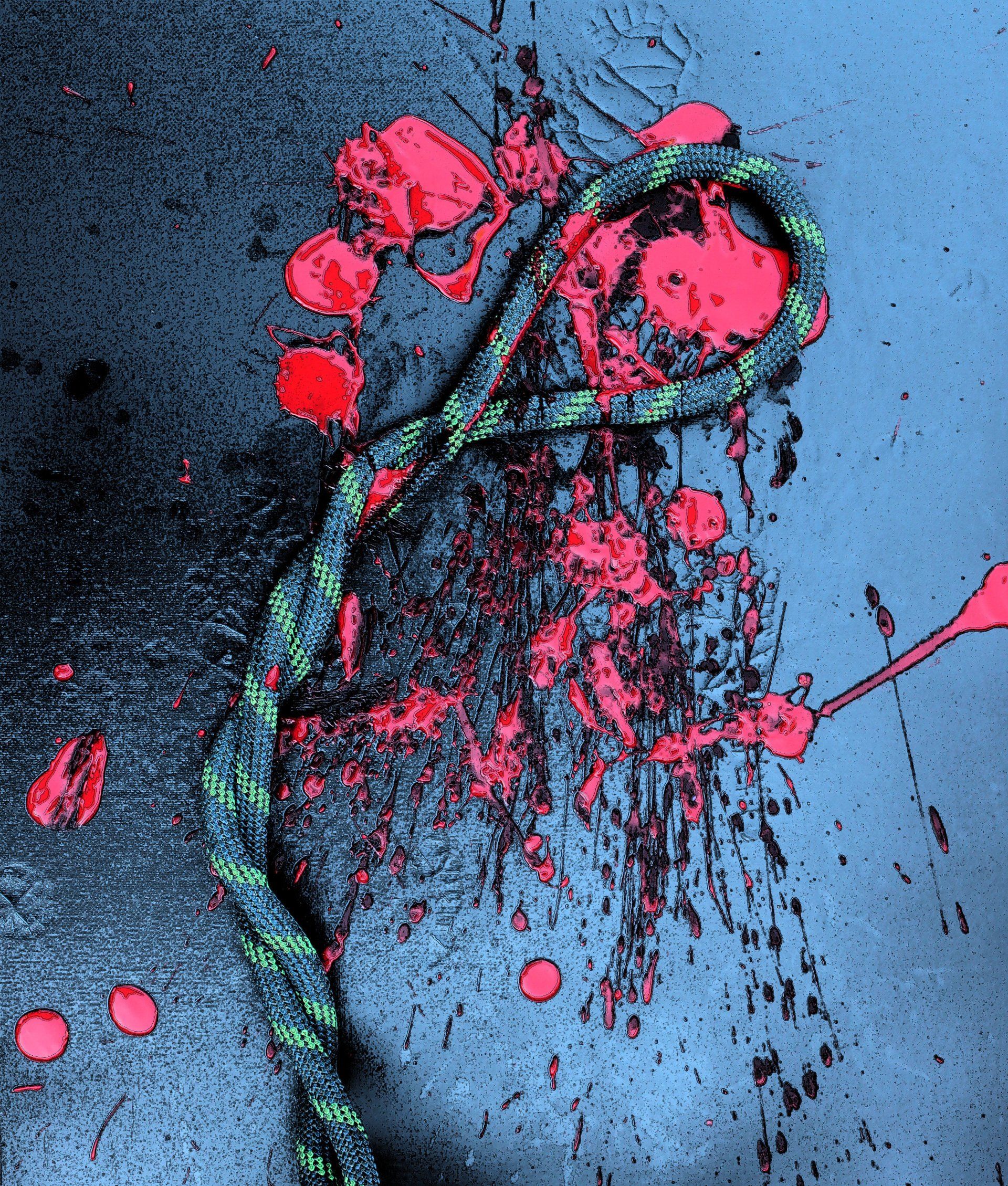

Doc requested the attire. The wispy red dress, the black tights and short black heels, lipstick and black curls bunched by a black hairband: she was the magician’s assistant. But she left the tights in the car and kicked the pumps off right before climbing out to the ledge. “Screw that,” she said, toes better to balance with. Stuart had looped and tied her wrists together with a climbing rope and checked the copper bracelets before she ducked out the window. He had forgotten to throw the rope down to the square, so he held her arm above the elbow as she crouched on the ledge, checked the landing, yelled “Rope!” and tossed the coil out into the air. She carefully stood and sidestepped along the ledge to press her back against the vertical slab of cement. He popped his head out and asked if she wanted anything.

“Um, no,” she laughed.

“I’ll be right in here, monitoring.”

“Check!” she said. She could hear herself dispersing into the void, carried away by winds that swirled around the square on a disc of pigeons circulating below. She was five stories high.

The chorus of fear and balance might be Don’t look down, but her balance was fine — her balance was duly recognized on playgrounds across old neighborhoods. She was good. Fear is the catalyst of a fall. Her shins itched a little for the brush of the dangling rope, and there were a few strong updrafts. With her hands tied and plunged in front of her by the weight of the rope, she thought of Marilyn Monroe on the subway vent.

She could watch Doc addressing the crowd sixty feet below her. So many were there already. A throng. He had achieved the critical mass where anything can be promised to a crowd and they’d stick around. But this was something else: a woman on a ledge tied to a rope, and the mechanism was all backwards, all upside down. She could only be pulled down into a free fall to an abrupt, catastrophic end. Doc, still talking over his shoulder to the audience in outlandish explanation, walked over and took up the dangling end of the rope. “Oh,” she said, feeling the tug. She twisted her feet a little wider and pressed her toes over the edge.

She could hear phrases drifting upward: An entire life in one’s hands, the whim of gods, the disproportionate power of a single moment, the privilege to feel in the fabric of a rope an entire life’s culmination. All this he offered them.

Most of the crowd were watching the monitors, only occasionally peering up to verify that the subject of the video was real. She swished her hair side to side. She could watch herself duplicated across a dozen monitors. She put one leg out and then the other. There was a time delay.

Doc held out the ends of the rope to any takers. Hands raised, several of them. This surprised her. So many were so convinced that they were party to an elaborate stunt that they couldn’t imagine culpability for a woman’s tragic death. Maybe Doc was right about the participation of the public in a show. The sublimation of reality had been complete. Planes never hit those buildings. Russian soldiers were paid actors and reports of school shootings satisfied 30-second spots between new ways to grout a bathtub and people dropping from ledges. Producers and audiences both feel the disappointment over tidal waves that never in video conform to the shape of our dreams, a smooth wall of dark water building from the deep into a monstrous curl, ready to swallow a city in its black, gaping maw.

The crowd beneath her watched on the bank of screens for what comes next.

She moved a leg. She brought out her arms and sent a ripple down the length of the rope. There was at least a one-second delay. She imagined herself falling in a slow, one-half rotation. She lands on her back — the crowd hears the radial, explosive clap, turns to the sound of the impact, and misses the whole thing on TV. She smiled at the comic potential.

Doc made his selection: a man in an oversized bucket hat, lost in a white sleeveless shirt and cinched into his baggy white shorts with a strap. The man was not having it, though. He didn’t volunteer; Doc picked him. He swung the rope back at Doc, but Doc was insistent and so he returned it to the man’s hands. The man refused again, pushed back emphatically, and threw both his hands into the air. Doc grabbed him by a raised arm and pulled him to the side for a word. Veronica watched all of this with some wonder, and pressed her toes around the edge, sending white bands of bloodletting compression across the surface of her feet.

The man in the bucket hat broke Doc’s grasp and was walking a circle in fretful thought. He circled back and grabbed the rope. She felt the tug in the rope. They were now connected.

It bothered her a little that he never looked up. He was pulling the rope taut against her wrists and then giving it slack as if it were a fishing line, all beneath his big hat and only turning now and then to watch the monitors. He matched what he did with what he saw on the screen. Every small tug she could feel the shimmy in her kneecaps. A half rotation would put her into a dive, and so she wondered, if the tug was hard enough, if she should just step off early to enlist the crumple zone of her legs. There was no chance any other way, headfirst or on her face.

She wondered if falling victims tense up their bodies before hitting the pavement. It was so strange to think of the crescendo of all that sound and you wouldn’t be there to hear it.

The man kept fishing with the rope, a slow dance between them separated by five stories, and the silence of the crowd told of their fascination. Directly below a couple of small girls — everyone is small from the ledge — were stretching their necks to see. That’s exactly where I’ll land, she thought. They’ll be flattened.

She began to question when the real tug would come when she heard a single whoop of a siren outside on 14th street. The man flung the rope and fled, mashing his hat on his head. Doc immediately seized the sandwich board and clapped it shut. There was a frenzied agitation of key players in the crowd. They had been activated. The bank of monitors disintegrated in seconds. Hand trucks were loaded and banners were ripped down. The rope dangling from Veronica’s wrists still twirled from being flung and it caught the legs and arms of Doc’s art students as they ran by in quick grabbing jerks. Two stout policewomen entered the square through the arched passageway. They swayed with belts of batons, revolvers, handcuffs and spray. Stuart popped his head out the window.

“Gotta go! Grab your rope!” She smirked at this, and sidestepped back to the open window just as firecrackers exploded at the north end of the square. The police felt for the sides of their belts in perfect unison. One called it in, and the other took a few cautious steps toward the volley of small explosions, scanning back and forth across the rapidly emptying square. Stuart grabbed Veronica’s hands and shielded her head from knocking into the top of the frame. He snatched a bag and they ran down the service stairs in a rattle of loose handrails.

It was only when Stuart stopped to remember where they parked that he saw Veronica hopping on her feet like she was running in place. The asphalt was searing in the sun. He offered his back. She hopped on and said, “Get!”

It took them three blocks and some laughable retracing to find Doc in the car waiting for them. He was delighted. Everything went as planned.