5.

Drowned

ON THE TOP DECK of the Lisa Fremont, the pillared speakers carried the dulcet tones of a rapper who sounded bored with himself. A refrain of a subtly changing, reiterating demand for Milk Duds.

The patrons, dressed in various interpretations of ‘semi-formal,’ some men in baseball t-shirts, most in buttons, and all the women in summer dresses, spent the majority of the float out and dinner trying different angles and facial expressions that would confuse Janus. Stuart watched from the railing. He noted the photographic smile. He mused. The reflex of the automatic smile begins with the demands of parents and is likewise preserved by deep mortal yearning, to be remembered smiling. So when near the end they’ll look for evidence of a time happily lived, they’ll have their proof. But what, thought Stuart, about the half second beyond the click of a button? What of the stock smile that recoils just as fast and vanishes in consternation at the inauthenticity of the event? Record a face at the half second beyond the photograph and then we’ll see it: the flash of doubt.

He looked down the edge of the railing to see Ms. Veronica Samir, untelevised, unpixelated, the subtle movement of ages, blinking into the breeze of a full sunset. She wasn’t mulling over the water she was about to plunge into, the swirling, propeller-chopped whorls and froth-tipped peaks of a highly trafficked river. She wasn’t looking for an entry point into the croc-infested Nile, but into the farther vapor of the Hellenic age. Her face in this era, he thought, would launch a thousand ships above the horizon, airships, new century zeppelins, inspired and electrified. He could see her profile vinyl-wrapped across the skin of futuristic hovercraft, tattooed across the ship like Hermes as heroine, her cheek bones as sleek and smooth as a Spartan helmet. Or is there in her a more Polynesian equivalent in the Capricorn cosmos? What is her genealogy, he wondered. This would be a good question to ask her. He strolled down the railing of the drifting river boat, and proposed the question. She didn’t move but held her chin into the wind — it wasn’t until he heard Doc’s boisterous laugh that Stuart relented his fantastic approach and admitted to himself that he’d not stepped a foot. He remained in the same spot, a freebie cup of diluted spirits in his hand.

Doc was doing pushups on the other side of the boat in exhibition for a number of men who left their wives to their photoshoots. The men laughed uproariously, bare-knuckle laughs, Hemingway’s boasts at the bar, laughter to challenge, compete, dare and scare off the presumptuousness and subtler contest of banter.

Veronica noticed two women in kayaks windmilling their paddles upriver, the bows piercing the brown waves and bucking blankets of water into their cockpits. They rode low in the rough water and she wondered if they needed rescuing.

Doc stood behind her. “Got your belt on?”

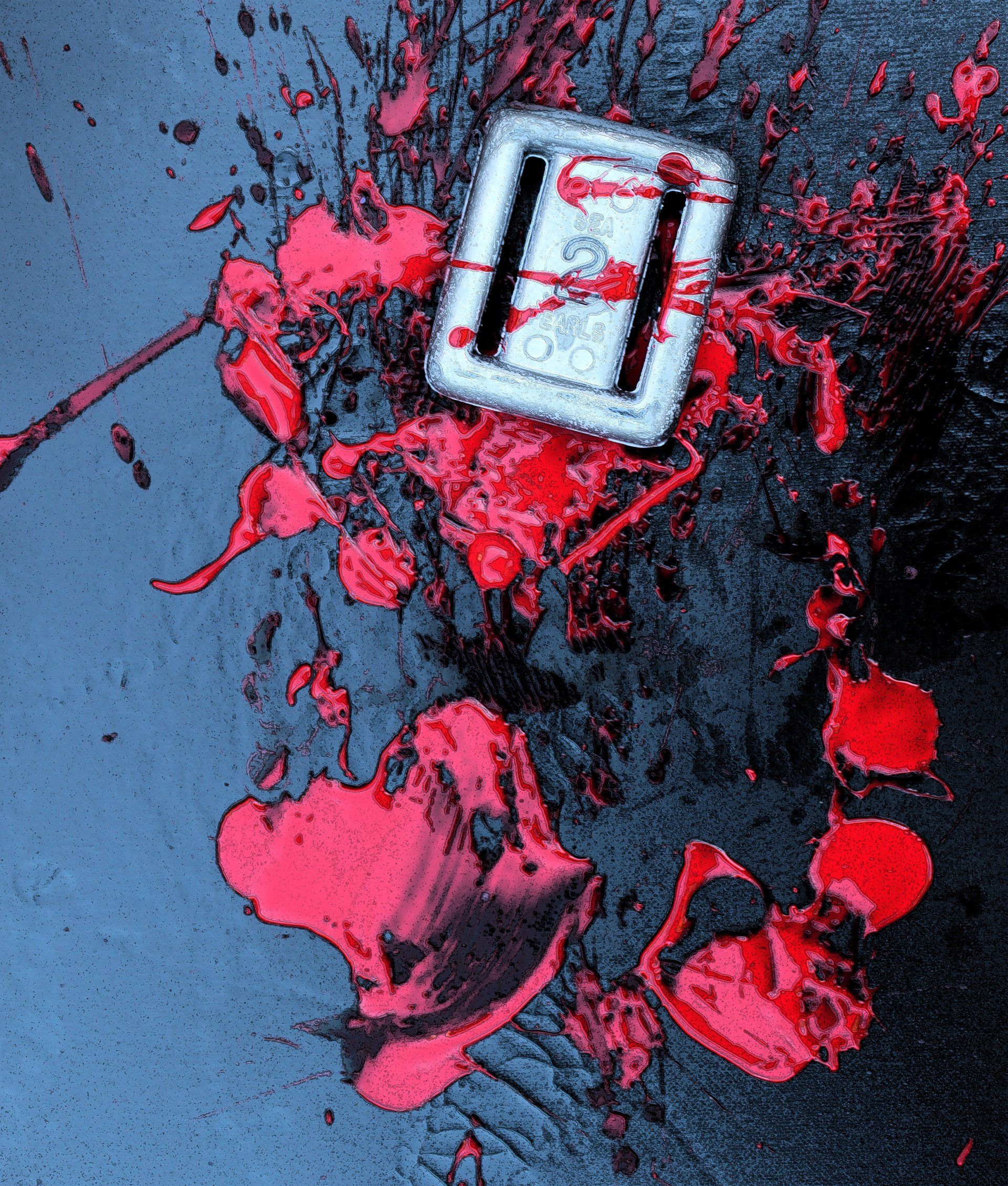

“That’s why I’m wearing this mumu instead of dressing cute like the other girls.” The light green print fell from her shoulders like a podium drape. Underneath she could feel the small bricks of weights down the webbing over her belly, across her hip, and diagonally up her back. Doc pushed his knuckle between her shoulder blades and felt for the clasp they had set in the gap above and below her reach. A cord looped around her other shoulder kept the clasp from slipping in either direction. He checked her bracelets as she scanned the crowd. Women stood shoulder to shoulder comparing tans on their forearms.

“Do you think they’ll save me?”

“Oh, I don’t know. There were some real braggarts in the crowd I was with. Care to make a speech before your tragic plunge? It could help.”

She scowled and stepped up to a storage box next to the railing, drawing the gown up her trailing calf. She balanced on the boat’s edge into the wind, the light green fabric whipping and twisting like a caught net or prayer flag. Doc thought of an impressionistic woman in no need of a parasol. He looked for any notice from the clumps of people down the deck. No one ever looks up, he thought, the only advertisements on ceilings are in cathedrals. He thought of how religiously they all stifle their insidious, latent mortal apprehensions with the daily wadding of trivial distraction, when the greater world is right there above them in the shape of a girl in the wind. He was formatting these words in his imagination, while down the port side his assistant was feeling them in a more inchoate, existential knock when they both turned from the inattentive crowd to find that she was gone.

They both panicked. She could already have disappeared down a seam of moving water.

Veronica’s first thought was the surprising warmth of the water. When she struggled to the surface, she could only look up, tilting her head back to breathe as she kicked her legs and furiously pumped her arms back-and-forth while foam and fabric collared her neck. She could see backlit shadows of heads appearing over the edge above her. She could see flashes of bulbs. Sound cut in and out. Someone was shouting, maybe Doc.

She could hear the drone of an engine cutting into the shouts of the man, and then only the drone underwater. Her hair lifted from her neck above her head and she could feel the fish skin of her dress gathering around her arms. She had imagined she’d see blue — blue Dickinson uncertain blue — but there’s no light down here. She kicked and pushed down volumes of water to slow her slide into an invisible column. Was it 15 seconds? she wondered. Someone fearless could keep count. She descended. She had been eager to see by these experiments if life, as they say, passes like a 1940s newsreel before her eyes, but she could only think in physical sensation. When can any person living ever think? Her lungs burned and she tried in vain to reach the clasp, but as she stretched and contorted for it, she felt the weights slip off and bash the tops of her feet. Almost immediately she bobbed to the surface.

She spat, pulled a tangle of hair from her face, and squeegeed the water from her eyes with her fingers. Women were treading around her, three or four. She laughed and said, “thank you!”

In the stern of the ship, she sat with Doc on a storage bench. “Not a blip,” he said. The crowd had returned to their stations at the bar. “Not a blip of your pulse until the moment, I gather, you hit the water and began treading furiously.” He patted her head with a towel as she rubbed her legs dry. “Not a blip besides the expected spike for physical exertion, and then the line turned downward a little as you continued to sink. What were you doing down there?

She laughed, “I don’t know! Thinking, I guess.”

“Thinking, ‘when am I going to be rescued?’”

“A little, but mostly about what I was thinking. I did wonder if I could reach the clasp, but when I reached my arms around, it was already gone.”

“A stranger to the rescue, in the nick of time.”

“A whole party of them at the surface!”

Doc left the towel on her head. He looked down the deck at all the people who had snapped back to their comportment, but with at least a new story to tell, or new captions. “You know, most people’s heart rates would stay at the limit not only for the ensuing wake of adrenaline, but stay just as high for all the attention they would suffer afterwards.”

She dried out her ears, folding the towel around serpentine locks of wet hair.

“We got some great coverage of this one,” said Doc.

“Mm,” she throttled with grinning suspicion.

Doc was looking at her from the side. He nodded, “Right,” and slapped a quick drum fill on his knees. “How do you feel about wild animals?”